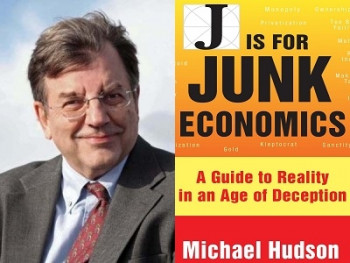

Book review: J is for Junk Economics by Michael Hudson

Michael Hudson is regarded by many as one of the world’s best economists because of his willingness to pierce the veil of deceit that passes for modern economic wisdom. His latest book J is for Junk Economics exposes much of modern economic thought as pure propaganda, says Moneyweb.

Michael Hudson is regarded by many as one of the world’s best economists because of his willingness to pierce the veil of deceit that passes for modern economic wisdom. His latest book J is for Junk Economics exposes much of modern economic thought as pure propaganda, says Moneyweb.In 2006 Michael Hudson, a former Chase Manhatten economist, warned of the coming mortgage bubble as an inevitable result of the debt explosion, but his warnings were brushed off as the murmurings of a spoiler.

J is for Junk Economics is his latest work, and is a follow-up to his previous book, Killing the Host. Junk Economics is discomfiting to those who profess to understand free markets. It is a full frontal attack on modern banking, monopoly privilege and the so-called rentier class that has siphoned wealth away from the working and middle classes to the already wealthy.

“The 2008 banking and junk mortgage crisis saw the United States and Europe save banks and bondholders, not their economies. While governments spent trillions on bailouts and ‘quantitative easing’ to save large creditors and speculators from losses on their bad loans and gambles, public and private infrastructure has been left to crumble and median wages are drifting down.”

The printing of new money in the form of “quantitative easing” is fire-hosed into the stock, real estate and bond markets to keep asset prices aloft.

Junk economics says Hudson, is the cover for all this. Dressed up in scientific jargon, it is little more than propaganda calculated to redistribute wealth upwards, reversing the policies urged by 19th century classical economists and reformers.

Hudson is an advocate of debt Jubilees of biblical reference, where unpayable debt was simply written off – usually by rulers seeking recruits for a new war or large-scale public works programme. The ravages of compound interest guarantee that our current debt burden can never be repaid, other than by more and more money printing. But that always ends in catastrophe, and is in fact the poison that has killed civilisations from Babylon to Greece and Rome.

The way we measure gross domestic product is fictionalised by the inclusion of unearned income such as interest and rent paid to the FIRE sector – finance, insurance and real estate. Exclude these rentiers (as they were known a century ago) and our GDP figures come crashing down. Hudson distinguishes between the “real economy” of factories and commerce from the financialised economy, though it is the latter which is exalted as the engine of economic growth. This is how the US economy has been deindustrialised, as factories moved to low wage countries such as China.

What about the perceived wisdom of budget surpluses so popular among World Bank types? Hudson points out that budget surpluses are achieved by raising taxes or cutting back public spending, “taking money out of the economy to pay bondholders.” Paying down public debt sucks money out of the economy, just as consumers servicing their bank loans leads to debt deflation.

Just as commercial banks create money electronically by lending, governments can do the same thing. Government budget deficits spend money into the economy, which is not inflationary when labour and resources are unemployed. This is in contrast to neoliberal economists who preach austerity, followed by bank bailouts when their disastrous policies inflate financial bubbles to the benefit of their constituency of bankers and bondholders. He fires broadsides at modern economists for enabling the dispossession of the 99%, and smears the Nobel Economic Prize is a PR campaign for “neoliberal junk economics”.

Tough stuff, but immensely entertaining. “It is time to throw down the gauntlet and accuse the rentier financial class deceptions of being what they are: economic fictions,” writes Hudson.

J is for Junk Economics is a dictionary of sorts, explaining the theories of Adam Smith to John Mills. Even the word “free market” has been twisted by modern interlopers to mean freedom to extract unearned rent or income. This is where Hudson is at his best. “To deter regulation, taxation or nationalisation – and even to gain public subsidy and government guarantees – lobbyists for the FIRE sector depict rent and interest as reflecting their recipients’ contribution to wealth, not their privileges to extract economic rent from the economy.”

Banks and real estate speculators derive unearned “rent” from the overall improvement in property values. A new access road funded by taxpayers increases the overall value of properties in the area. Banks and speculators extract this value in the form of higher mortgage payments and commissions. The phenomenon was well known in the 19th century by Karl Marx and classical economists such as John Stuart Mill. The recommended solution to this was for governments to tax the increase in land values away, rather than hand it over to rentiers, and reinvest this back into the community to promote further prosperity. To count this unearned rent as part of national income is to pretend that banks are providing a real economic product (as opposed to bank lending for a factory, for example, which leads to tangible economic output).

Another misconception tackled by Hudson is the notion that classical economists such as Adam Smith stood for free markets and opposed government interference. What they actually opposed were governments controlled by the landlord aristocracy dominating tax policy, resulting in Britain’s House of Lords taxing labour and industry instead of land and finance.

At a time when there is discussion of starting a state-owned bank in SA, the architects should be required to read this book rather than listen to the solicitations of bankers. China’s state-owned banking system, long derided by Western analysts for its abstruse accounting, has been a major pillar of that country’s economic miracle. Rather than taxpayer-funded bailouts, as occur in the West when banks fail, Chinese banks simply write down debt.

You can watch some of Hudson’s debates and presentations on Youtube to get a sense of his staggering knowledge of economic history.