SA faces its "Trump" moment

South Africa looks like it is facing its own "Trump" moment. In this excellent analysis, Capital Economics suggests that President Zuma may have survived last week's no confidence vote, but his end is nigh nonetheless. Zuma's game plan is clearly to find a friendly successor ahead of the ANC's elective conference in December next year. Then he may choose to resign knowing he will likely escape prosecution for corruption. The succession battle will likely provide fodder for a newly energised opposition ahead of the presidential election in 2019. South Africa is ready to turn its back on the Zuma era.

South Africa looks like it is facing its own "Trump" moment. In this excellent analysis, Capital Economics suggests that President Zuma may have survived last week's no confidence vote, but his end is nigh nonetheless. Zuma's game plan is clearly to find a friendly successor ahead of the ANC's elective conference in December next year. Then he may choose to resign knowing he will likely escape prosecution for corruption. The succession battle will likely provide fodder for a newly energised opposition ahead of the presidential election in 2019. South Africa is ready to turn its back on the Zuma era.In a report out today, Capital Economics says political tensions surrounding South African President Jacob Zuma will not ease following the embattled president’s victory in yesterday’s vote of no confidence. They will, in fact, probably increase as the waning of the president’s final term in office prompts a succession battle within the ruling African National Congress (ANC). The risk of rand-moving surprises will remain considerable in 2017. A more populist turn by the party could also have significant economic impacts.

Zuma dodges another bullet

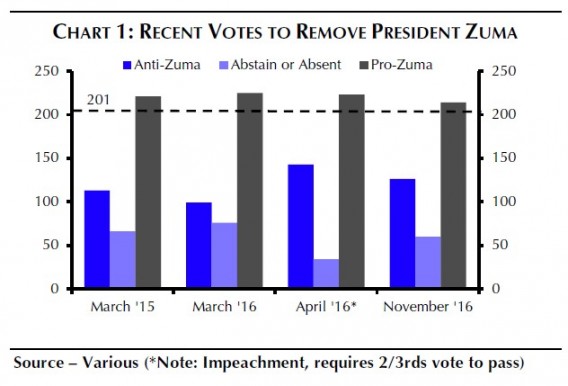

It was no surprise yesterday’s no confidence motion received far fewer than the 201 votes needed to remove Mr. Zuma. The ANC, after all, controls a solid majority of the body’s 400 seats.The vote was, however, far from a ringing endorsement of the embattled president. While the ANC holds 249 seats, just 214 members voted to keep him in office. Several high-profile ANC MPs (including the respected finance minister) abstained. Just 126 MPs supported the motion, which was the third attempt so far this year to remove the president from office. (See Chart 2.)

President Zuma has long been a controversial figure in South African politics. Since 2006 he has faced charges of both corruption (which were deferred) and rape (he was found not guilty). In March, South Africa’s constitutional court found that the president had acted illegally when he ignored a state auditor’s report demanding that he repay public money used to improve his personal home.

The latest attempt to dislodge Mr. Zuma concerns allegations of corrupt ties between the president and the influential Gupta family, which runs businesses linked to several state firms (and which, until recently, employed Mr. Zuma’s son).

The scandal – which has, inevitably, been deemed “Gupta

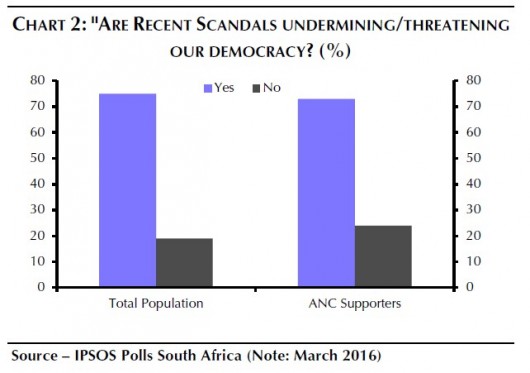

gate” – has touched a nerve. A poll taken in March found that 75% of South Africans called it a “threat to democracy”. In a blow to the ruling party, this sentiment was shared by a 73% of self-described ANC supporters. (See Chart 2.)

gate” – has touched a nerve. A poll taken in March found that 75% of South Africans called it a “threat to democracy”. In a blow to the ruling party, this sentiment was shared by a 73% of self-described ANC supporters. (See Chart 2.)Political ructions, market costs

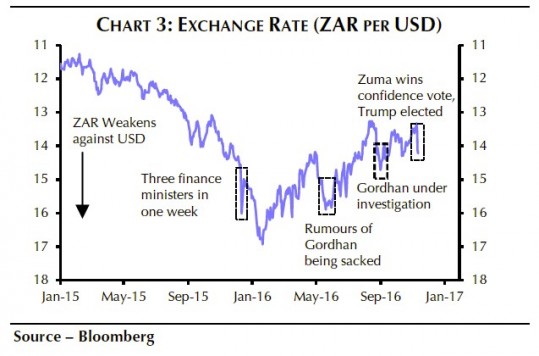

The escalating scandals surrounding President Zuma have weighed heavily on South African markets over the past year. The influence of the Guptas is widely seen as a key cause of Mr. Zuma’s December 2015 decision to replace his respected finance minister with a relative unknown. This caused the rand to drop by 9%

Since then the currency has been frequently buffeted by President Zuma’s allies attempts to depose Finance Minister Pravin Gordhan, whom Mr. Zuma was forced to appoint after pressure from the ANC and key business leaders. (See Chart 3.)

The removal of Mr. Gordhan would cause the rand to fall even further than it did in December 2015. Such a move would also almost certainly lead credit agencies to cut South Africa’s foreign credit rating to junk (an S&P ratings review, scheduled for December, is probably finely balanced as it is).

Staying power

As yesterday’s vote shows, Mr. Zuma’s critics still lack the votes to remove him from office. Even were future investigations to result in more allegations of corrupt activities by Mr. Zuma and his associates, we doubt that this would be enough to change the fundamental parliamentary arithmetic. (He has already been criticised in two official reports and found guilty of violating the constitution.)

Keeping it inside the family

Constitutionally-mandate term limits, however, demand that President Zuma’s time in office ends in June 2019. As his presidency winds to a close, we believe that tensions will increasingly focus on struggles within the ANC, rather than between the ANC and the opposition.

The battle to replace Mr. Zuma poses a significant risk to the economy. While intra-ANC politics are frequently opaque, we expect that the campaign will probably result in a struggle between a more pro-Zuma candidate (who might shield the former president from prosecution) and a ‘change’ candidate (who would seek to distance the party from its controversial ex-leader).

Mr. Zuma clearly has a strong incentive to encourage the party to choose a friendly successor. So it is possible that he would seek to use his influence as president to affect the result. This could include surprise cabinet reshuffles, new spending programmes, or even politically-motivated prosecutions. A significant struggle within the ruling party could paralyse decision-making or make policymaking increasingly erratic and unpredictable.

Mr. Zuma clearly has a strong incentive to encourage the party to choose a friendly successor. So it is possible that he would seek to use his influence as president to affect the result. This could include surprise cabinet reshuffles, new spending programmes, or even politically-motivated prosecutions. A significant struggle within the ruling party could paralyse decision-making or make policymaking increasingly erratic and unpredictable.Things will come to a head at the ANC’s elective conference, which is currently scheduled for December 2017. It is important to note that this meeting will select a successor to Mr. Zuma in his role as head of the ANC, not as president of the republic. The timing of Mr. Zuma’s exit from the presidency itself will probably depend on who the conference chooses to replace him.

If he succeeds in arranging a close ally as a successor, the president might resign pretty quickly, secure in the knowledge that the investigative and prosecution authorities will still be in trusted hands.

The selection of someone seen as less friendly to his family’s interests, on the other hand, could prompt Mr. Zuma to hold onto his state role for as long as possible in order to delay a politically-motivated prosecution. A “co-habitation” between Mr Zuma (as state president) and a rival (as head of the ANC) could result in policy uncertainty and political tensions within the ruling party.

While the succession battle is unlikely to be fought along ideological lines, it may still send a signal about the future direction of economic policy in South Africa. A win for a candidate who is seen as being pro-Zuma would suggest policy continuity. Potential figures from this camp could include AU head Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma (who is also Mr. Zuma’s ex-wife) or ANC treasurer Zweli Mkhize.

A victory for Deputy President Cyril Ramaphosa would probably be welcomed by the markets as a shift towards more investor-friendly policy-making. The former mining executive – who also helped to negotiate South Africa’s transition to democracy – has avoided being implicated in any of Mr. Zuma’s latest scandals. His ties to Lonmin, the owners of a mine at which almost 50 miners were shot in 2012, could harm his chances.

Whoever the ANC chooses, the party will probably face the most competitive presidential election since the end of Apartheid in 1994. In August 2016 the ANC recorded its worst-ever electoral result, losing control of several municipalities (including Johannesburg) to the Democratic Alliance (DA). Things could yet get worse for the ANC. The struggle to select a successor may provide further bad publicity for the ANC by focusing attention on Mr. Zuma’s scandals. We also expect that economic growth will remain very weak. (See Chart 4.)

Indeed, he or she may actively run on a programme of ‘change’ and ‘renewal’. If the election is close, the ANC may adopt a more populist platform in order to shore up its support. With the DA gaining ground among middle class urbanites, the ANC might try boosting spending in poorer rural areas to shore up its support there. Costly job-creation schemes or a more progressive tax code could prove popular in a country where more than a quarter of the population is unemployed and vast racial wealth inequalities persist. Indeed, given the ANC’s current scandals revolve around ties to wealth business figures, the next leader may choose to highlight the party’s socialist roots. A rise in pro-poor spending could boost growth in the short-term. But with government debt already elevated and inflation near the top of the SARB’s target range, a spending spree would significantly increase economic vulnerabilities.

Indeed, he or she may actively run on a programme of ‘change’ and ‘renewal’. If the election is close, the ANC may adopt a more populist platform in order to shore up its support. With the DA gaining ground among middle class urbanites, the ANC might try boosting spending in poorer rural areas to shore up its support there. Costly job-creation schemes or a more progressive tax code could prove popular in a country where more than a quarter of the population is unemployed and vast racial wealth inequalities persist. Indeed, given the ANC’s current scandals revolve around ties to wealth business figures, the next leader may choose to highlight the party’s socialist roots. A rise in pro-poor spending could boost growth in the short-term. But with government debt already elevated and inflation near the top of the SARB’s target range, a spending spree would significantly increase economic vulnerabilities.Conclusion

The opposition’s efforts to remove President Zuma from office are unlikely to succeed. But the controversial president’s time in office is coming to a close, and we expect that political tensions in the country will rise over the coming years. Succession struggles within the ANC probably pose a greater threat to South Africa’s economy than have the tensions between President Zuma and his finance minister.