Public Service Act, 1994

Public Service Act, 1994

R 385

Public Finance Management Act, 1999 (Act No. 1 of 1999)Understanding and Using this ActIn Year Management, Monitoring and Reporting2. Production & Interpretation of Reports |

In-year management, monitoring and reporting

Each department will have compiled a three-year strategic plan, and the first year of this (the operational plan) will include the service delivery indicators and costs which, once approved by the legislature, becomes the annual budget. The executive authority must ensure that the accounting officer’s performance agreement is consistent with the operational plan, and that the KPIs reflect the fact that implementation must start as soon as the financial year begins.

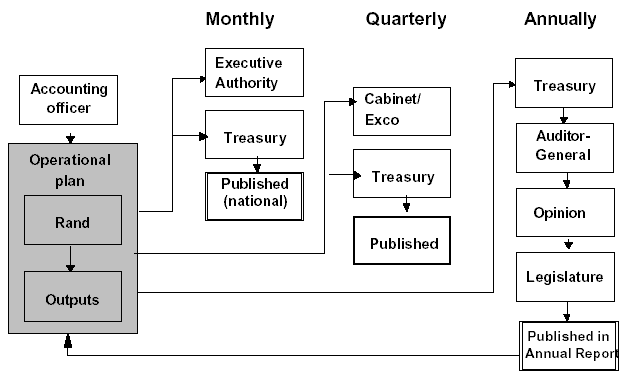

Once the financial year begins, the accounting officer must submit regular monthly monitoring reports to the Minister or MEC and the relevant treasury. The PFMA specifies a variety of progress reports, monthly, quarterly and at year-end, with different responsibilities for executive authorities and accounting officers (those for accounting officers are summarised in Annexure B). The requirements are illustrated in the diagram above, and are detailed in the remainder of this chapter.

These reports will focus on performance against budget and against service delivery plans, and will alert managers when remedial actions are required. The onus to take such actions is put squarely on the manager and not on the (relevant) treasury. The treasury’s role will shift away from the traditional micro-control approach, which required even mundane matters to be referred to it for approval.

Whilst the Act focuses on financial reporting, (as financial data are leading indicators of performance) the accounting officer is also expected to include non-financial indicators to the executive authority, which will normally be programme-specific and produced quarterly (this will be a formal requirement from April 2002).

Internal control measures such as internal audit will ensure that the accounting officer can be more proactive, and problems dealt with timeously. This approach will also assist the external auditor.

The monthly monitoring reports will be consolidated and published in the national Government Gazette, in line with international best practice. These reports will facilitate the compilation of the year-end financial statements and the annual report, which completes the accountability cycle.

Monthly reports

The accounting officer must submit to the relevant treasury and executive authority within 15 days of the end of each month, information on:

| • | the actual revenue and expenditure for that month, in the format determined by the national Treasury |

| • | projections of anticipated expenditure and revenue for the remainder of the current financial year in the format determined by the national Treasury |

| • | information on conditional grants received and actual spending against them |

| • | information on all transfers |

| • | any material variances and a summary of actions to ensure that the projected expenditure and revenue remain within the budget. |

Provincial statements to the national Treasury

In addition, the provincial treasury must submit a statement of transactions affecting its revenue fund (in the prescribed format) to the national Treasury before the 22nd day of each month. The head of the provincial treasury must certify that the information has been verified.

Quarterly reports

The national Treasury will publish in the Government Gazette, at least quarterly, a statement of the revenue and expenditure of each of the ten revenue funds, showing actual performance against the budget for each vote.

Information on grants made under the DoRA must be reported in terms of that Act, which requires that the accounting officer effecting transfer payments must submit a report to the relevant treasury within 15 days after every quarter, outlining per organisation all the funds transferred up to the end of that quarter.

Annual report

The accountability cycle is completed by the production and publication of an annual report, which reviews performance and achievement against the plan and budget approved by the legislature at the start of the year. The Act requires each department to publish an annual report that ‘fairly presents’ the state of its affairs, its financial results and position at the end of the financial year, and its performance against predetermined objectives. The annual report is the subject of another ‘Best Practice’ Guide in this series, and is not considered further here.

The Reporting Process

Conceptually, there are a number of steps in the process of converting the millions of individual transactions that occur as a result of government activities into the information to be published monthly. While the major focus is usually on the reports generated by the accounting system at the end of each month, the stages which surround the production of the reports are equally important, and these are summarised in the diagram attached as Annexure C. (While the process may be clear, a number of problems remain to be solved in order to improve the quality and reliability of the information, and the issues to be addressed over the coming months are considered in Section 4 of this Guide.)

Accounting officers are not expected to understand all the technical details of these processes, but from a managerial perspective, they will need to appreciate the key stages; these are the accounting procedures which have to be completed at the end of each month, the comparison of actual revenue and expenditure to that anticipated in the budget, and the projections for the remainder of the year.

In order to improve accountability, each Accounting Officer is required to sign the report for his or her department before it is submitted to the relevant treasury and the executive authority.

The key stages in this process are considered in more detail in the paragraphs below.

Month-end procedures and reports

In any large organisation such as a government department, a sequence of complex and interlinked accounting transactions must be completed at the end of each period in order to produce a ‘result’ for the period. While the detail and volume of these transactions may vary considerably from department to department (and from accounting system to accounting system), the nature of the tasks to be completed will be consistent, and will include the requirement to undertake reconciliations, check the allocation of transactions, clear errors and suspense items, balance various types of accounts, etc. These processes may well appear tedious, but a failure to complete them on a routine basis will lead to major complications and delays at the end of the financial year, and possibly expose the accounting officer to a charge of financial misconduct for not producing the department’s accounts within the prescribed period of two months.

In order to meet it’s obligations, the National Treasury requires monthly information from departments by the 15th of the next month, and hence in future, these month-end procedures will have to be completed at the very latest by the 10th day of every month. A detailed example (taken from a Provincial government) of the tasks to be completed within each department appears as Annexure D.

Completion of the procedure outlined above will allow the ‘books to be closed’, and a monthly result produced in the form of ‘actual expenditure and revenue’. This information is usually shown on a cumulative basis, against the budget for the corresponding period in order to indicate any variance (each of the major different systems in operation has a variety of user manuals available, and the salient points of FMS, BAS and PERSAL appear as Annexure E). It is crucial that managers understand the reasons why variances have arisen, and this is discussed in detail below.

Formats and Projections

Examples of the reports to be submitted to the relevant treasury in terms of the PFMA and DoRA are shown at Annexure F.

These formats require more than an indication of (and explanation for) variances between the actual result for the period and that budgeted: they require a projection to the end of the financial year. In the past, this projection was often simply presented as the difference between the annual budget and actual expenditure (or revenue) to date; in effect managers assumed that any unspent amounts on their budget would be used by the end of the year. In other words, managers were implicitly stating that the plan upon which their budget had been based would be achieved exactly, despite the fact that this plan had been compiled up to 10 months before the start of the financial year, and may have been overtaken by events, or that the evidence (in the form of recorded variations in the year-to-date performance) demonstrates that events may not be on track.

This unthinking approach is not acceptable, and is one of the most crucial changes in attitude sought by the PFMA. It is essential that managers address the in-year management concepts outlined in the introductory section of this Guide. These are:

| • | What has happened so far? |

| • | What do we think will happen to our plan for the rest of the year? |

| • | What (if any) actions do we need to take to achieve our agreed plan? |

| • |

The month-end report reflects what has happened so far. It must be noted that variances between the actual result and that budgeted arise for different reasons, and it is vital that the underlying reason for each variation is identified before any projection for the remainder of the year can be made.

In general, the reasons variations arise are as follows:

| • | Errors – large scale accounting systems are prone to errors at the data input stage (for example, incorrect codes are used, resulting in misallocations between cost centres or line items); |

| • | The report is incomplete as some transactions have not been captured at the time the report was produced (for example, a batch of invoices was not received and processed before the closing date); |

| • | The budget ‘profile’ - that is the anticipated timing of particular events during the year – proved to be inaccurate. For example, at the time the budget was approved, it was assumed that vehicles would be serviced in July, and this did not happen until August – resulting in an apparent underspending in the July report); alternatively, the budget ‘profile’ may simply have divided the total figure for the year into 12 equal instalments while the actual pattern of expenditure is seasonal (for example, electricity, where expenditure is likely to be higher in the winter). It must be stressed that the exercise to produce an accurate month-by-month profile of the annual budget is an area where accounting officers can make an immediate improvement in the financial data available to them; |

| • | Actual events do not accord with those planned (for example, projects are slow to start, and will not be completed within the financial year). This is the type of variation that will require the greatest attention from management. |

Any projection must be based on an understanding of which of the four reasons mentioned above has given rise to a variation (and of course, even a zero variation to date does not mean that the projection will equal the remaining budget). Based on this understanding, each manager will be able to apply his or her mind to predicting what will happen to their plan over the rest of the year. For example, will a delay in the award of a tender result in a capital project running into the next financial year with a consequent underspending this year? Similarly, the financial consequences of all aspects of the plan can be anticipated and a realistic projection calculated. Finally, each manager must consider what (if any) action must be taken to achieve the agreed plan: this is considered below.

Commitments

One of the key factors in developing any projection is a consideration of the ‘commitments’ that a department may have entered into to date, for example, orders issued for goods or services which have not yet been received. Clearly, committed amounts reduce the balance available for expenditure in the remaining portion of the year and must be brought into the calculation of any projection.

Summary

The PFMA promotes the need for in-year management of resources, and requires, with immediate effect, accounting officers to act as managers, and ensure effective in-year management mechanisms are in place. Accounting officers must monitor progress on the department’s operational plan (which includes the budget), and produce, consider and act on monthly and quarterly reports, which are to be submitted to the executive authority and the treasury. Systems and processes already exist for monitoring and reporting monthly budgetary performance, but accounting officers will have to scrutinise the (financial) data, including data on grants and transfers, produced before signing off on the reports required by the Act.

Financial data is a leading performance indicator (i.e. it is normally available before other nonfinancial data), and should ideally be accompanied by non-financial indicators, and both should be submitted to Executive Authorities and Cabinet or the Provincial Executive Committee on a quarterly basis. From April 2002, this will be an obligation of the PFMA (although accounting officer are free to begin immediately).

Accounting officers are expected to use international best practice; this will be monitored by the relevant portfolio committee and by SCOPA. Failure to implement best practice may expose the accounting officer to disciplinary proceedings. For example, should unauthorised expenditure occur and the accounting officer be unable to demonstrate that he or she had made use of the monthly reports required by the Act and had taken appropriate remedial action, the relevant treasury may wish to institute charges of financial misconduct.